Questions from a reader

What is the history of the disembodied hands and heads in Fra Angelico's Mocking of Christ?

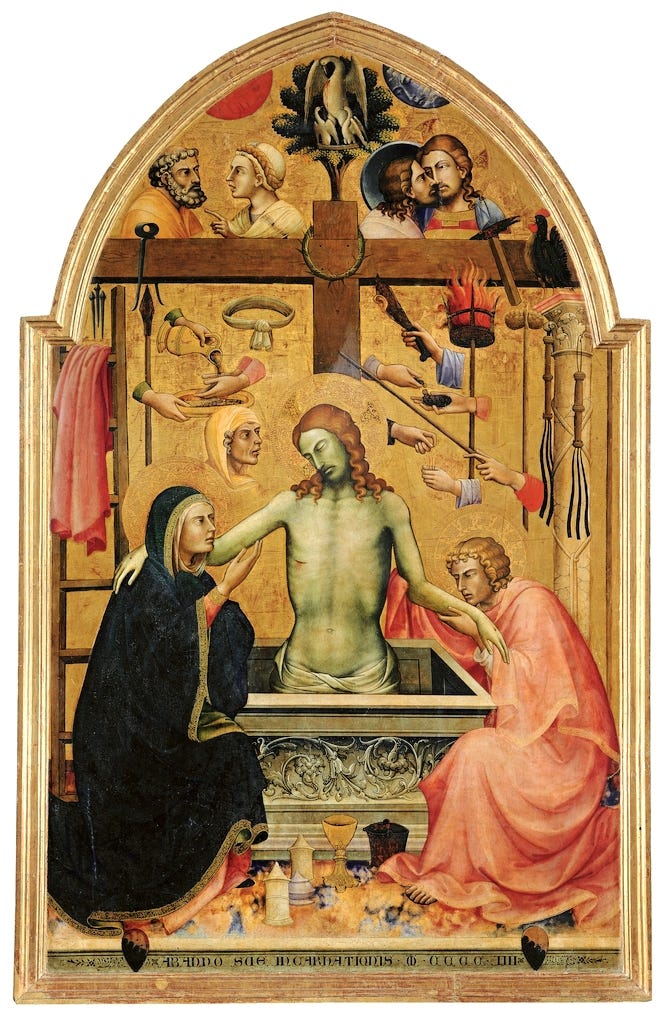

The post Lessons from my professor: focusing on the beautiful in devastating times focused on a haunting image of the Mocking of Christ painted by the Florentine artist Fra Angelico at the end of the 1430s for the Dominican friary of San Marco in Florence. Among its most striking features, some of which seem to anticipate modernist abstraction, are the disembodied hands that slap, poke, and prod Jesus as part of his humiliation during the episode in which Roman soldiers crowned him with thorns.

A reader has inquired about this almost surreal motif, as well as the isolated figure of a man shown only as a head, mockingly doffing his cap to the “king.” Her question inspired me to look more deeply into the history of this iconography.

Examples of the figure of Jesus with symbols of the Passion can be found in works by a number of artists in Angelico’s orbit, most importantly, the Camaldolese monk-painter Piero di Giovanni, better known as don Lorenzo Monaco (ca. 1370-1425).

Many scholars now agree that if don Lorenzo was not Angelico’s first teacher, that he certainly was one of his earliest collaborators and mentors, and it seems likely that Angelico’s use of disembodied Passion symbols was inspired by earlier devotional images painted by the elder monk.

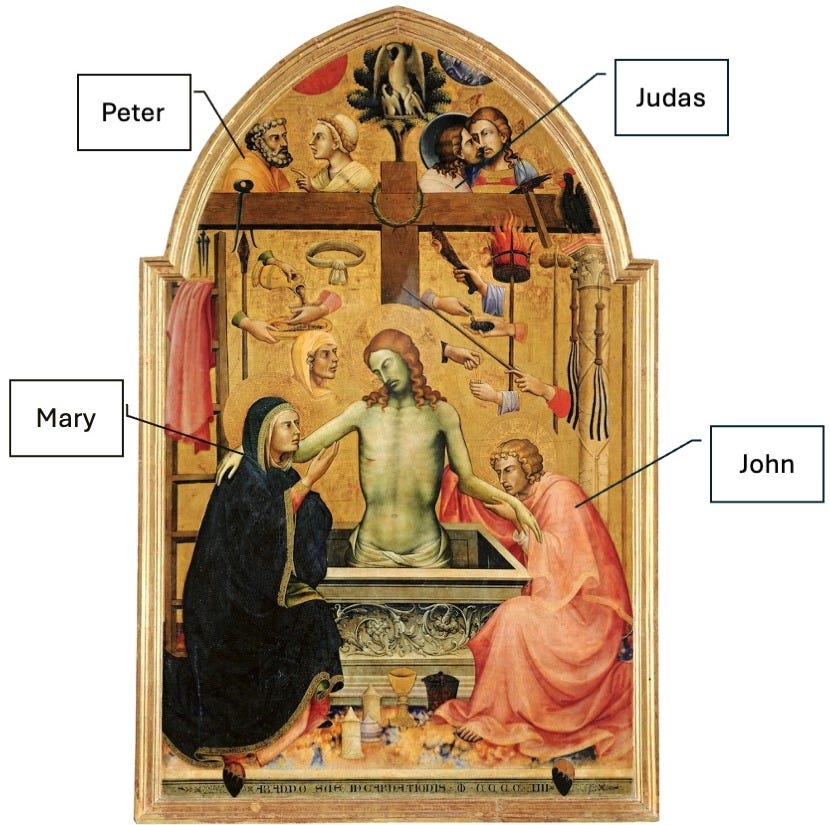

Lorenzo Monaco’s image, a large cusped panel almost eight feet high, is crowded with figures and objects as compared to Angelico’s slightly smaller fresco, which has been stripped down to its bare essentials. Angelico presents an abbreviated narrative of the mocking of Jesus at the hands of his Roman captors prior to his execution by crucifixion. Lorenzo Monaco, on the other hand, encapsulates the before and after of this sacrifice, as we see the crucified Jesus rise out of his tomb below the decontextualized cross. Sometimes called the Man of Sorrows, this image shows Jesus embraced by his mother Mary and his favorite apostle John the Evangelist, both of whom stood by him at the Crucifixion when his other disciples had fled. Above the crossbar we see an abbreviated Kiss of Judas at the right and the Denial of Peter at the left, under the sun and moon representing the darkened heavens at the moment of Jesus’s death. Hands, heads, and weapons allude to other tortures suffered by Jesus prior to his crucifixion.

Angelico, however, presents only a few specific references to the Mocking of Christ. The tomb is not present, for Jesus still lives, but it is alluded to by the large marble slab under his seat. The intended audience for the fresco — the community of Dominican friars resident at San Marco in Florence — only needed a few cues to enter into deep contemplation of Jesus’s difficult path to his death, as modeled by the seated St. Dominic. Moreover, other frescoes in the dormitory relate preceding and successive narrative moments to the mocking, while Lorenzo Monaco encapsulates the entire Passion in one image.

Paid subscribers may read on for a description of each symbol in Lorenzo’s picture and to see additional examples of this picture type.

If you’d like to support independent art-historical writing with or without a subscription, donation options are available.

We will start at the vertical center of the image and work our way through it from the top:

The body of Jesus is shown from the hips up, rising out of his marble tomb that is decorated with the Roman motif of an acanthus scroll. Wearing only a meager loincloth, we can see the wound in his right side (our left) that resulted from his side being pierced with a spear during his crucifixion, which you can see at the left just above Mary’s head. His eyes are closed, raising questions as to whether he is still deceased, but he appears to embrace his mother with his right hand, while she appears to support his bicep with hers. Similarly, John holds Christ’s left elbow and forearm as he leans to kiss his teacher’s hand in a gesture of honor and humility. Do Mary and John support Jesus? Or, does he support them. Of course, the answer is: both things can be true.

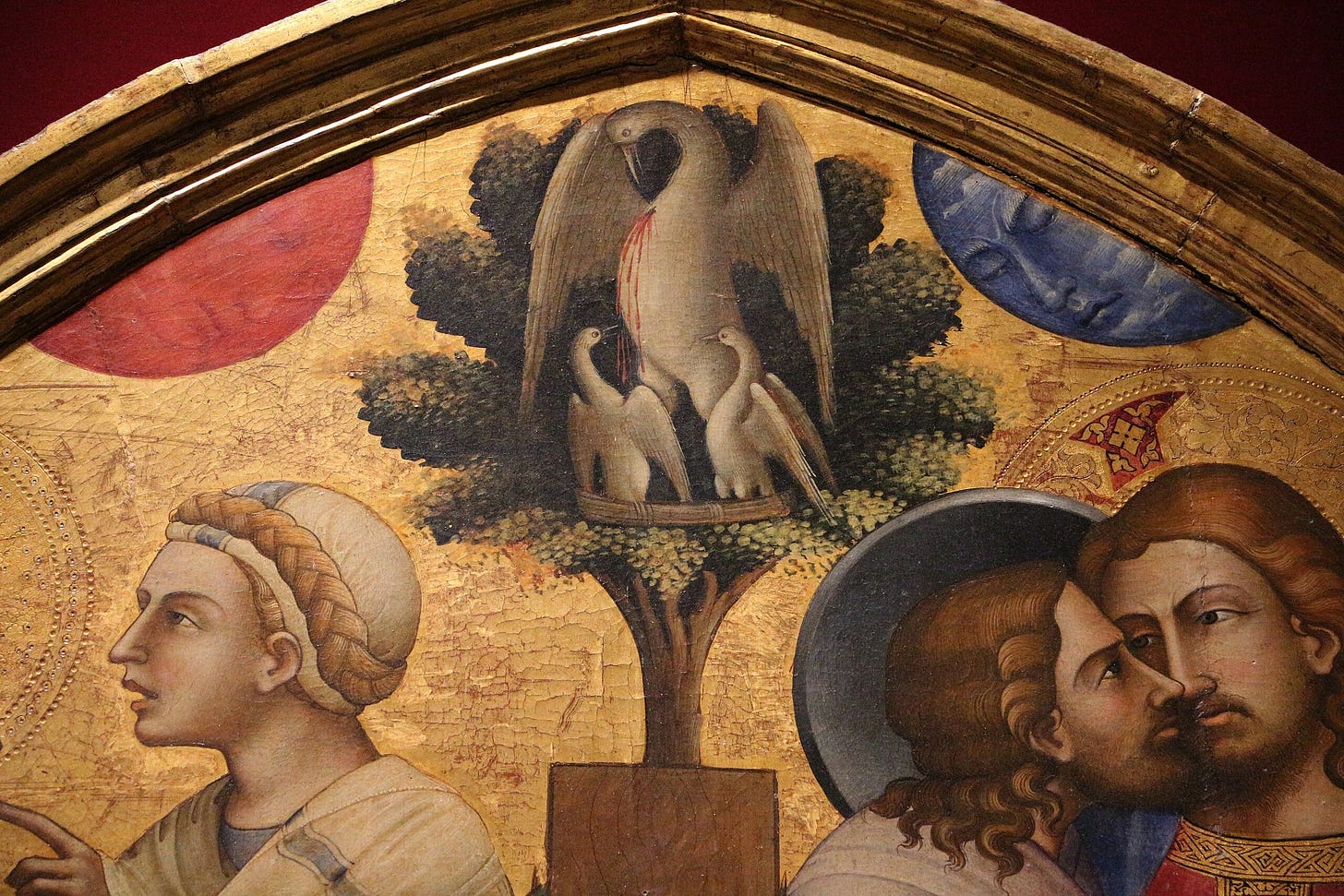

Typical of Western art, Christ appears on the central vertical axis of Lorenzo Monaco’s composition, drawing the viewer’s eye to him again and again. This vertical centrality is further emphasized by the vertical post of the cross, a traditional mode of execution in the ancient Roman world. Its crossbar becomes the support for several so-called instruments of the passion as well as two abbreviated narratives and the Christological symbol of the Pelican and her chicks.

According to the Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture (1996), the mother pelican fed her young by pecking her own breast until it bled, feeding her chicks with her blood, just as Christ would come to nourish his followers with his during the Eucharist. (For more on the Eucharist, also called Communion, see this explanation from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops). Flanked by the sun and the moon, she crowns the cross on which Jesus shed his blood as a sacrificial act for the forgiveness of mankind’s sins.

Below her on the right we see Judas greeting Jesus with a kiss, the traditional form of salutation in the ancient world, and in much of Europe today. This was the agreed-upon sign by which Judas would identify Jesus to the Roman authorities — a traitorous act that led to the arrest, mocking, and execution of his teacher. Judas’ halo is painted in shades of gray indicating his traitorous descent to the dark side.

Below Judas, to the left of Christ’s halo, we see the thirty pieces of silver being given by a disembodied Roman’s hand into that of Judas Iscariot, the disciple who had been the most devoted among the Twelve, but ultimately betrayed him, sending him to death, which in turn made possible the salvation of mankind.

I will follow up soon with more analysis and identification of this fascinating picture, continuing our close reading of Lorenzo Monaco’s dense symbolic program, but I would love to hear from you how frequently you would like to receive new posts from me. Are you annoyed that the story ends right here? Have you had enough for today and would like to process this lesson before taking on more? Too much detail? Not enough? You may send me a direct message or comment on the post. Thank you!

Anne, the length and the amount of detail of your entries is just right for me. I don’t expect daily entries and will likely look for something from you every few days to once or twice a week.