What is Art?

Is it only in the eye of the beholder?

Before we begin exploring prehistoric art next week, I want to take a moment to discuss what makes something a work of art in the first place.

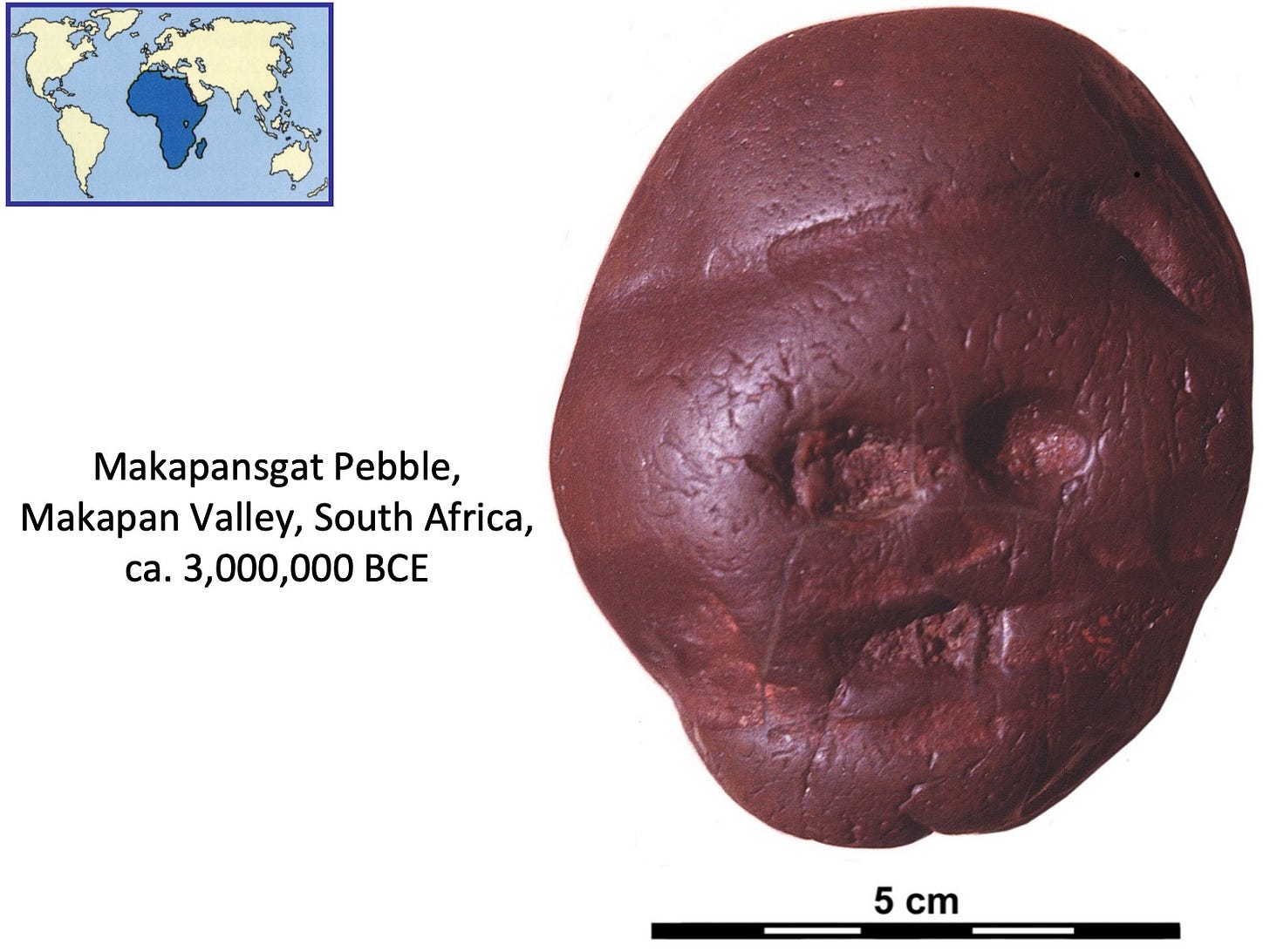

Look at the illustrated object below:

What do you see? A rock? A face? A very old prune?

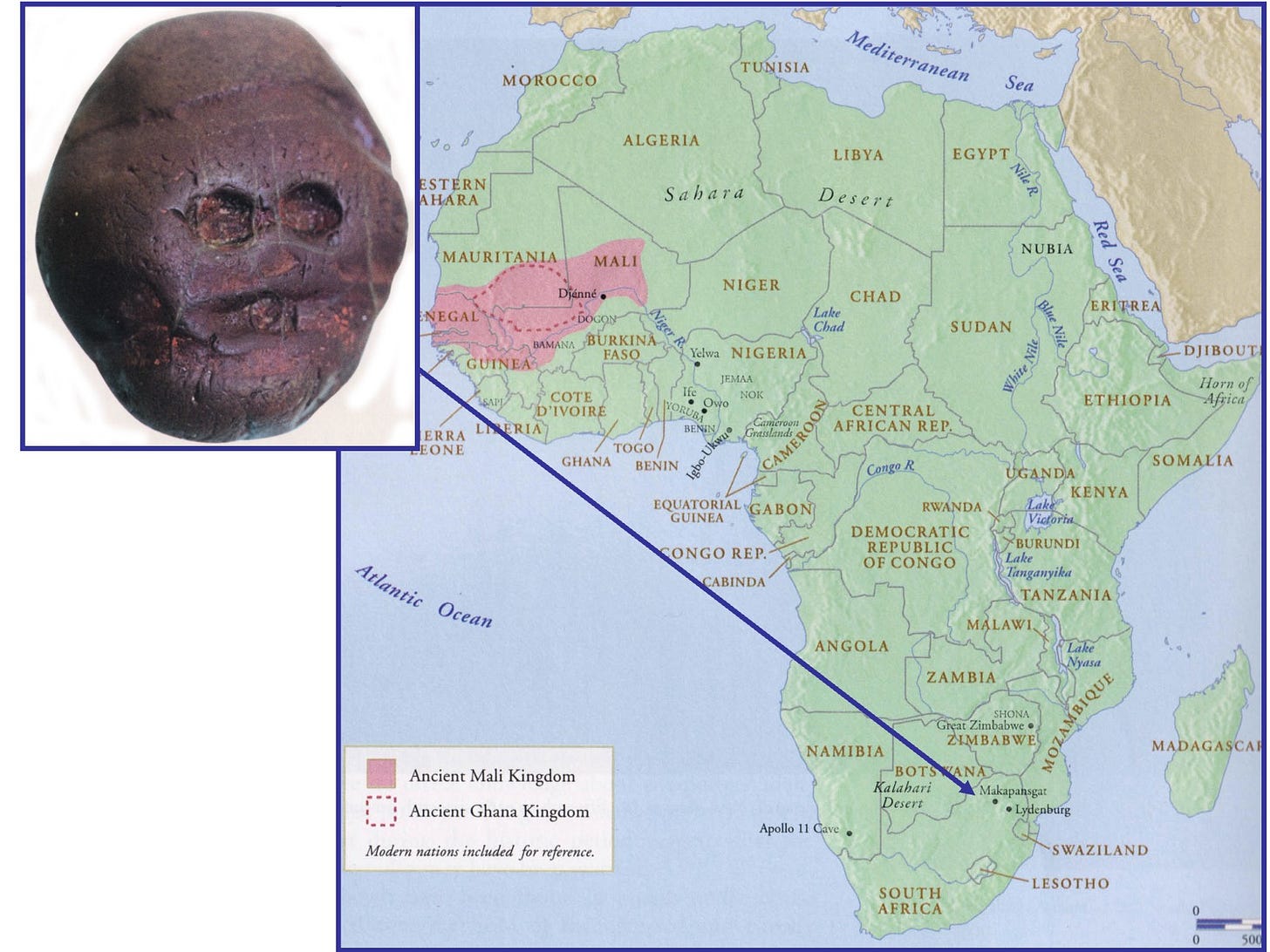

The so-called Makapansgat Pebble was found in 1925 in a cave in Makapansgat, South Africa, alongside bones of Australopithecus africanus, a predecessor of modern humans living in this region about 3,000,000 years ago.

Yup, that’s three million years ago.

Five centimeters at its widest point, the Makapansgat pebble would fit comfortably in the palm of your hand. It is a reddish-brown stone known as jasperite. With its pair of round pockmarks over an oblong indentation, the pebble resembles a human-like face.

Does it count as a work of art?

Microscopic technical studies have revealed that the stone was worn down by water, and all of its details are natural rather than deliberately carved or manipulated. That is, we have a naturally occurring, found object rather than something changed by the intervention of hands or tools.

manipulate | məˈnipyəˌlāt | verb [with object] 1 handle or control (a tool, mechanism, etc.), typically in a skillful manner

Our basic distinction between art — a word derived from the Latin word ars meaning skill — and a found object is whether any intervention has taken place to change its appearance through intervention with the hand (the Latin manus), i.e. manipulation.

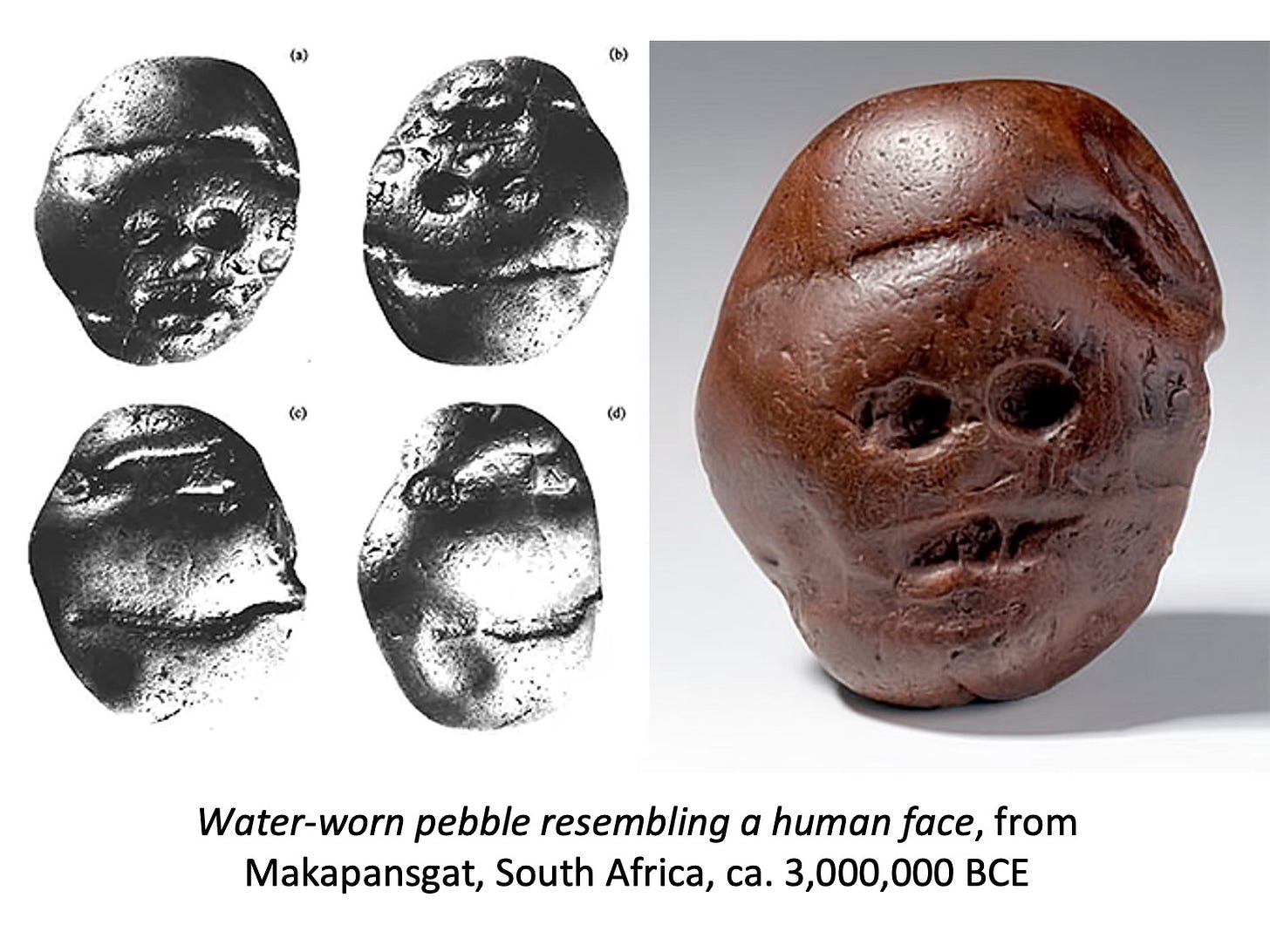

This object also reminds us that our understanding of the object is dependent on the photographs we have available to us, as this comparison of views shows:

The pebble is typically presented, as in the eleventh edition of Gardner’s Art through the Ages (Harcourt, 2001, p. 2, fig. 1-1), in a frontal or slightly three-quarter view, as seen on the right above. This orientation was given to the pebble by its discoverer, the local schoolteacher Wilfred Eitzman. However, the stone can be turned in numerous directions, as seen on the left, and has been called the “pebble of many faces”: one with a large cranium, another with a large jaw and toothless smile, and if we turn it over, we see resemblances of eyes and a mouth again.

For paid subscribers: read on for more about how this humanoid pebble, though not a work of art, may suggest a very early aesthetic sense and a desire for collecting and treasuring objects, an important precursor to the making of art.

You’ll also be able to ask questions or leave comments.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this water-worn pebble is that the closest source of this type of stone is twenty miles away from the cave where it was found, leading archaeologists to believe that it was discovered and purposefully kept, carried for miles by its owner.

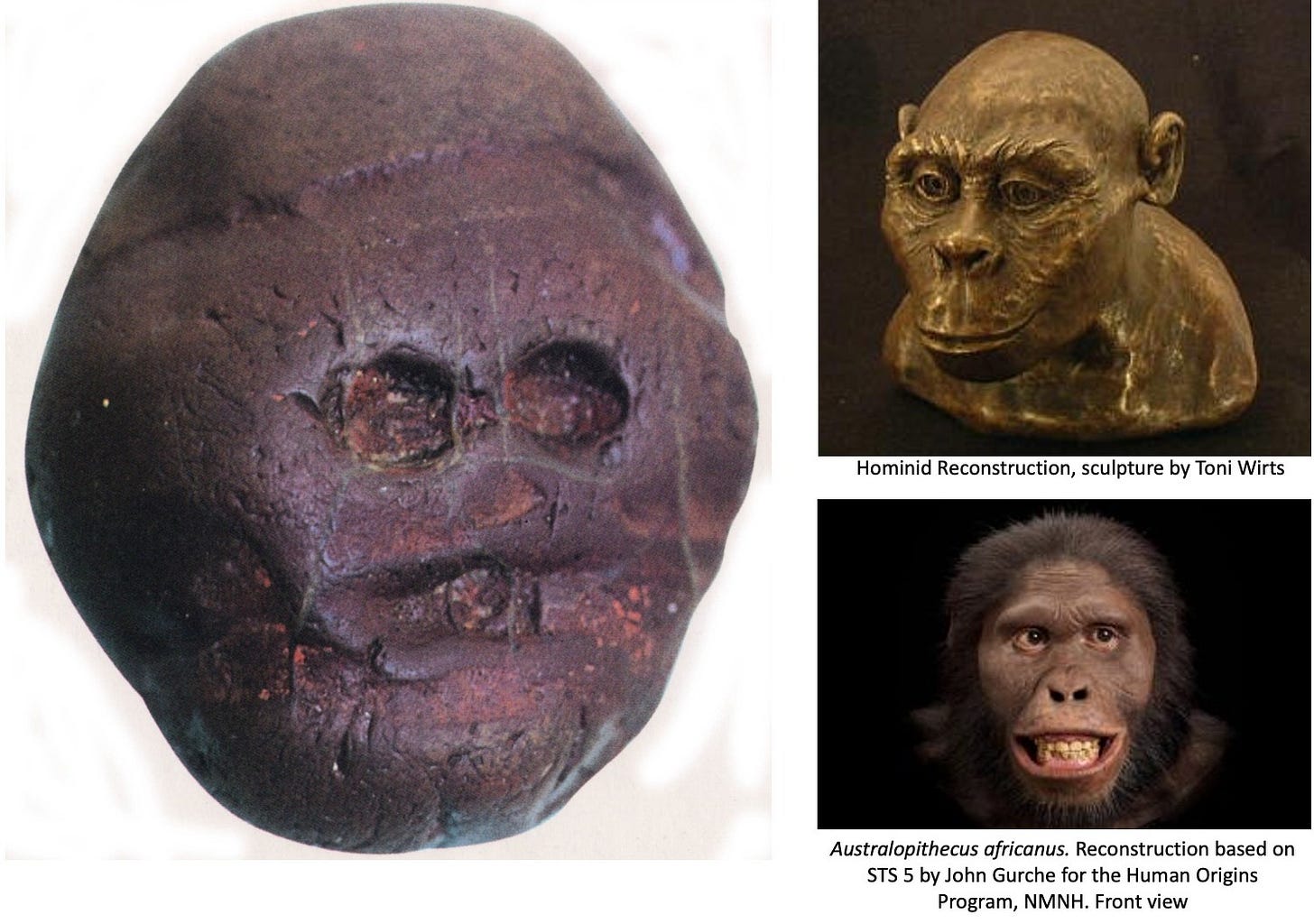

The bones found alongside the pebble have been identified as Australopithecus africanus — a hominid ancestor of the same family, but a different genus and species than modern humans, who lived in southern Africa in the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene epochs some 3.3 to 2.1 million years ago.

Our pebble-owner would have walked upright, had teeth similar to humans, but a much smaller brain. Archaeologists have surmised that the ridges and pockmarks on the surface of the Makapansgat pebble echoed our ancient ancestor’s face. He (or she) recognized the abstracted face and felt the stone was worth keeping. We call this type of object a “manuport” because it was picked up by a manus, or hand, and carried (portare) somewhere else.

While many questions remain about this pebble and how it found its way from its natural source at least twenty miles from its findspot in the Makapansgat cave, we can feel comfortable concluding that a very early hominid had an aesthetic interest and aesthetic sense. While not the same as art making, the pebble shows early evidence of the recognition of images in the natural environment. We will have to wait at least 2½ million years before we find evidence of artistic production or creation.

Well, really only until next week when we explore some of the oldest known artworks on earth. Until then, happy looking!

The meaning of art changes over time, as we know. I found your example of that marvelous rock face from so long ago to be really interesting. The idea that such an early human might respond to an image (apparent face etched into the stone) as being recognizably akin to his or her own face - this is astonishing.

This is a wonderful springboard for your next installment. I can’t wait!